Nekpijn [richtlijn]

B.5 Analyse

De fysiotherapeut gebruikt de informatie uit de anamnese en de bevindingen uit het lichamelijk onderzoek om de nekpijn en mogelijk andere stoornissen in functies en anatomische eigenschappen, de beperkingen in activiteiten en/of participatieproblemen, en de onderlinge samenhang hierin te analyseren.

Op basis van de verzamelde gegevens kan het gezondheidsprobleem van de patiënt in kaart worden gebracht.

Hiertoe moeten de volgende vragen beantwoord worden:

- Van welke graad nekpijn is er sprake?

- Is er een normaal of afwijkend beloop van de klachten?

- Valt deze patiënt in de subgroep traumagerelateerde of werkgerelateerde nekpijn?

- Zijn er prognostische factoren (psychosociale, persoonlijke en omgevingsfactoren) aanwezig die een afwijkend beloop van de klachten kunnen verklaren en zijn deze beïnvloedbaar door fysiotherapie?

- Is er een verband tussen de beperkingen in activiteiten en/of participatieproblemen en de nekpijn of andere stoornissen in lichaamsfuncties en anatomische eigenschappen, en is dit verband beïnvloedbaar door fysiotherapie?

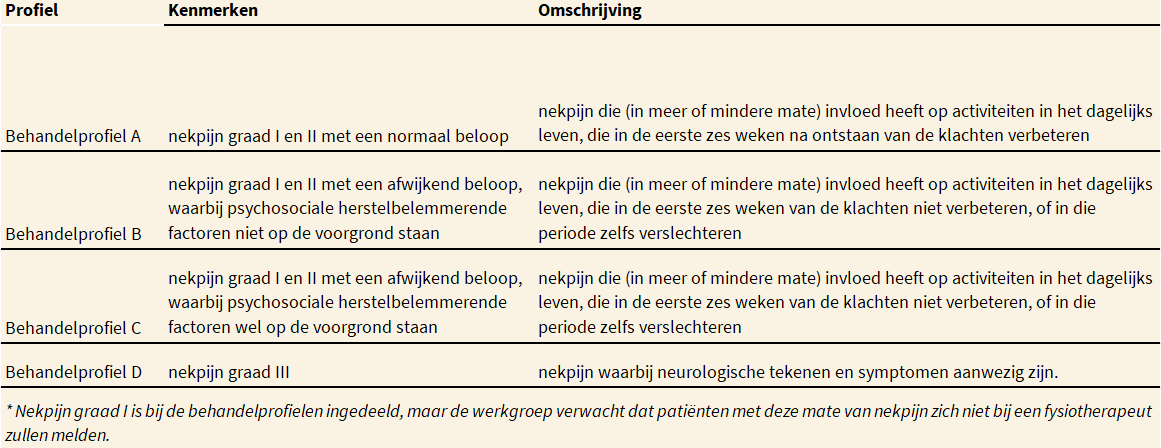

De werkgroep heeft vier behandelprofielen ontwikkeld op basis van de bevindingen in de literatuur over patiënten met nekpijn. Op grond van het antwoord op de hiervoor geformuleerde vragen, is het mogelijk om vast te stellen of fysiotherapie geïndiceerd is en aan de patiënt een van de vier behandelprofielen bij nekpijn toe te kennen.

Deze behandelprofielen zijn ingedeeld op graad van de nekpijn, het beloop van de klachten (normaal vs. afwijkend) en de aanwezigheid van psychosociale herstelbelemmerende factoren (wel vs. niet dominant aanwezig).

Psychosociale factoren spelen een belangrijke rol bij een afwijkend beloop van de klachten en zijn daarom medebepalend voor de keuze van het behandelprofiel (behandelprofiel B vs. C). Hoewel de werkgroep verwacht dat patiënten met nekpijn graad I, vanwege het normale beloop van de klachten, zich niet bij een fysiotherapeut zullen melden, is deze volledigheidshalve toch aan een behandelprofiel toegekend (behandelprofiel A). De behandelprofielen zijn schematisch weergegeven in de volgende tabel.

De Behandelprofielen bij patiënten met nekpijn.

Behandelprofielen

De werkgroep beveelt aan om bij patiënten met nekpijn de hierna beschreven indeling in behandelprofielen toe te passen, op basis van de anamnese en de bevindingen uit het lichamelijk onderzoek.

Tijdens de analyse dient onderscheid gemaakt te worden tussen nekpijn graad I, II en III.

De fysiotherapeut gebruikt de informatie uit de anamnese en de bevindingen uit het lichamelijk onderzoek om de ernst van de pijn, de beperkingen in activiteiten en/of participatie, en de samenhang hierin te analyseren. Op basis van de verzamelde informatie wordt het gezondheidsprobleem van de patiënt in kaart gebracht.

Op grond van de verzamelde gegevens zal de fysiotherapeut kunnen vaststellen of de klachten van de patiënt trauma- of werkgerelateerd zijn. Als de fysiotherapeut vermoed dat er sprake zal zijn van vertraagd herstel op grond van de anamnese, beoordeelt de fysiotherapeut of de prognostische (herstelbelemmerende of herstelbevorderende) factoren beïnvloedbaar zijn door fysiotherapie, en of de behandeling uitgevoerd kan worden volgens de richtlijn.

Ook stelt de fysiotherapeut vast of er een verband bestaat tussen de beperkingen in activiteiten en/of participatieproblemen en de nekpijn of stoornissen in lichaamsfuncties en anatomische eigenschappen, en of dit verband beïnvloedbaar is door fysiotherapie.

B.5.1 Prognostische factoren voor vertraagd herstel

Het is voor fysiotherapeuten essentieel om kennis te hebben van de prognose van de nekpijn en de aanwezigheid van prognostische factoren die een rol spelen bij het herstel. Deze kennis is nodig om te bepalen of er een indicatie is voor fysiotherapie en, indien dit het geval is, voor het bepalen van een behandelstrategie. De methodologische kwaliteit van de vele studies die zijn uitgevoerd naar potentiële prognostische factoren voor de duur van nekpijn is doorgaans echter te laag om duidelijke conclusies uit de resultaten te kunnen trekken.41

Uit een grote survey is een verschil gebleken tussen de huidige stand van de wetenschap en de dagelijkse praktijk bij het prognosticeren van nekpijn.46

Prognostische factoren voor nekpijn die gelden in de algemene populatie

Uit onderzoek is gebleken dat een voorgeschiedenis van musculoskeletale aandoeningen en een hogere leeftijd gerelateerd zijn aan een slechte prognose.22,41 Andere studies suggereren dat psychosociale stress mogelijk een negatieve invloed heeft op het beloop van nekpijn; deze negatieve invloed is mogelijk groter dan de invloed van de fysieke variabelen.45 In tegenstelling tot wat algemeen gedacht wordt, blijkt reguliere fysieke activiteit geen invloed te hebben op de uitkomst, met als uitzondering regelmatig fietsen, dat een voorspeller is van een slecht beloop.22,41,46

Uit een recente systematische review blijkt dat psychosociale factoren, zoals angstvermijding en passieve copingstrategieën, in grotere mate bijdragen aan een slechte prognose dan fysieke factoren.46 Uit een andere review bleek dat meer sociale steun, een copingstijl met zelfgeruststelling, optimisme en geen noodzaak om sociaal te zijn een positieve invloed hebben op het beloop van nekpijn; deze factoren hebben mogelijk weer een grotere invloed dan psychosociale factoren, waaronder in deze studie worden verstaan: psychologische gezondheid, copingstijlen en de behoefte om te socialiseren.22

De invloed van degeneratieve veranderingen, genetische factoren en compensatiestrategieën, potentiële prognostische factoren is nog geen onderwerp van onderzoek geweest dat voldeed aan de eisen die aan goed wetenschappelijk uitgevoerd onderzoek gesteld kunnen worden.22

Prognostische factoren die een rol spelen bij werkgerelateerde nekpijn

Er is matig tot hoog niveau van bewijs op basis van twee systematische reviews, dat het hebben van een voorgeschiedenis van nekpijn of andere musculoskeletale aandoeningen een prognostische factor is voor een slecht beloop van de nekpijn.40,41,47 Daarentegen is er matig tot hoog niveau van bewijs, op basis van twee systematische reviews, dat reguliere fysieke activiteit niet geassocieerd is met een betere prognose.40

Een systematische review heeft laten zien dat werkgerelateerde karakteristieken, zoals het aantal arbeidsuren, zwaar tillen, bovenhands werken, werkhouding en werktempo geen voorspellers zijn voor aanhoudende of recidiverende pijn.40 Tevens bleek dat bij chronische nekpijn hoge werkeisen (zich moeten haasten, meerdere taken tegelijkertijd moeten uitvoeren of vaak onderbroken worden tijdens het werk) voorspellend kunnen zijn voor aanhoudende chronische pijn (hoog niveau van bewijs).40

Voor het merendeel van de factoren die zijn gerelateerd aan de werkplek of aan fysieke eisen die aan het werk worden gesteld, bestaat geen wetenschappelijk bewezen relatie met het herstel van de nekpijn. Mensen die weinig invloed hebben op hun werksituatie lopen een grotere kans om na vier jaar opnieuw nekpijn te rapporteren dan mensen die wel invloed hebben op hun werksituatie.40 Iemand die fysiek werk verricht, heeft een zes keer zo hoge kans op arbeidsverzuim van meer dan drie dagen dan mensen die hoogopgeleid zijn, of een leidinggevende of administratieve functie bekleden (hoog niveau van bewijs).40

Prognostische factoren die een rol spelen bij traumagerelateerde pijn

Bij traumagerelateerde nekpijn zijn de volgende prognostische factoren gerelateerd aan een vertraagd herstel (met een hoog niveau van bewijs): een hoge pijnintensiteit (hoger dan 55/100, gemeten met een Visual Analog Scale (VAS) of de Numeric (Pain) Rating Scale (N(P)RS), een hoge mate van nekgerelateerde beperkingen in activiteiten (hoger dan 15/50, gemeten met de Neck Disability Index, NDI), symptomen van posttraumatische stress bij aanvang, catastroferen, hyperesthesie voor kou, hyperalgesia en een voorgeschiedenis van andere musculoskeletale aandoeningen.47 Er zijn aanwijzingen dat ook een passieve copingstijl gerelateerd is aan een slechte uitkomst (matig niveau van bewijs vanwege inconsistentie van de uitkomsten).41,47

Daarnaast blijken bij traumagerelateerde nekpijn de volgende factoren niet geassocieerd te zijn met de uitkomst: angulaire deformiteit van de nek (scoliose of een afgevlakte cervicale lordose), aanrijding vanaf de achterzijde, positie van de bestuurder, het hebben zien aankomen van de aanrijding, aanwezigheid van hoofdsteun, hogere leeftijd (boven de 50 jaar) en of het voertuig stilstond tijdens de aanrijding (hoog niveau van bewijs).47

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat andere factoren, zoals angst, depressie of persoonlijkheidskenmerken gerelateerd zijn aan een slechte uitkomst (laag niveau van bewijs vanwege de lage kwaliteit van de studies en de inconsistentie van de uitkomsten).47

B.5.2 Premanipulatieve besluitvorming

Indien de manueel therapeut overweegt om een cervicale manipulatie toe te passen, dient hij zich bewust te zijn van het mogelijke risico op cervicale arteriële disfunctie (CAD).

Vanwege dit mogelijke risico heeft de NVMT een standpunt over de aanbevolen premanipulatieve besluitvorming gepubliceerd, zie hiervoor https://nvmt.kngf.nl.

B.5.3 Het toekennen van een behandelprofiel

Op basis van de literatuur en expert opinion heeft de werkgroep voor de behandeling van patiënten met nekpijn vier behandelprofielen opgesteld, die richting geven aan het fysiotherapeutisch handelen bij patiënten met nekpijn graad I t/m III. De informatie die nodig is voor het kiezen van het juiste behandelprofiel is verkregen tijdens de anamnese. Daarbij dient opgemerkt te worden dat patiënten met nekpijn graad I zich zelden aanmelden voor fysiotherapeutische behandeling; voor de volledigheid zijn deze patiënten echter wel in de richtlijn beschreven.

Behandelprofiel A is opgesteld voor patiënten bij wie de nekpijn een ‘normaal beloop’ heeft. De behandelprofielen B en C zijn opgesteld voor patiënten met nekpijn graad I en II, bij wie het beloop van de nekpijn afwijkend is. Behandelprofiel B is opgesteld voor patiënten met een afwijkend beloop zonder dominante aanwezigheid van psychosociale herstelbelemmerende factoren. Behandelprofiel C is opgesteld voor patiënten met nekpijn graad I en II bij wie psychosociale herstelbelemmerende factoren wél dominant aanwezig zijn. Deze tweedeling was een wens van het werkveld, en wordt in de KNGF-richtlijn Lage rugpijn ook gehanteerd.

Behandelprofiel D is opgesteld voor patiënten met nekpijn graad III. Gezien de mogelijke ernst van de onderliggende pathologie kan de fysiotherapeut ten aanzien van patiënten met dit profiel eventueel eerst contact met de huisarts opnemen.

BehandelprofielenDe werkgroep beveelt aan om bij patiënten met nekpijn de hierna beschreven indeling in behandelprofielen toe te passen, op basis van de anamnese en de bevindingen uit het lichamelijk onderzoek.

|

1. Wees PJ van der, Hendriks HJM, Heldoorn M, Custers JWH, Bie RA de. Methode voor ontwikkeling, implementatie en bijstelling van KNGF-richtlijnen. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2007.

2. Vries C de, Hagenaars L, Kiers H, Schmitt M. Beroepsprofiel Fysiotherapeut. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2014.

3. IASP. IASP pain terminology. Beschikbaar via: http://www.iasp-pain.org/am/template.cfm?section=general_resource_links&template=/cm/htmldisplay.cfm&contentid=3058. Geraadpleegd op 8 febr 2014.

4. Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A, Bone, et al. Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S5-7.

5. Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Cote P, Carragee EJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S14-23.

6. Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Weiner SS, Hurwitz EL, Peloso PM, et al. Assessment of neck pain and its associated disorders: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S101-22.

7. Bogduk N. Regional musculoskeletal pain. The neck. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13(2):261-85.

8. Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Guzman J, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S52-9.

9. Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, Tulder MW van, Riphagen II, Vet HC de. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(3):307-19.

10. Lees F, Turner JW. Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. Br Med J. 1963;2(5373):1607-10.

11. Thoomes EJ, Scholten-Peeters W, Koes B, Falla D, Verhagen AP. The effectiveness of conservative treatment for patients with cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(12):1073-86.

12. Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-9.

13. Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994;117 (Pt 2):325-35.

14. Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, Boninger ML, Delitto A, Allison S. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(1):52-62.

15. Rodine RJ, Vernon H. Cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review on treatment by spinal manipulation and measurement with the Neck Disability Index. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(1):18-28.

16. Thoomes EJ, Scholten-Peeters GG, Boer AJ de, Olsthoorn RA, Verkerk K, Lin C, et al. Lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for cervical radiculopathy in conservative intervention studies: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1459-70.

17. Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009;147(1-3):17-9.

18. Kooijman MK, Barten JA, Leemrijse CJ, Verberne LDM, C. V, Swinkels ICS. Fysiotherapie - Top 10 klachten (ICPC 2013). Beschikbaar via: http://www.nivel.nl/nzr/top-10-klachten-icpc-0. Geraadpleeg op 8 febr 2014.

19. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163-96.

20. Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(6):783-92.

21. Picavet HS, Schouten JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC(3)-study. Pain. 2003;102(1-2):167-78.

22. Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Velde G van der, Haldeman S, Holm LW, Carragee EJ, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in the general population: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S75-82.

23. Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll D. The epidemiology of neck pain: what we have learned from our population-based studies. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2003;4(47):284-90.

24. Green BN. A literature review of neck pain associated with computer use: public health implications. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2008;52(3):161-7.

25. Hogg-Johnson S, Velde G van der, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S39-51.

26. Stahl M, Mikkelsson M, Kautiainen H, Hakkinen A, Ylinen J, Salminen JJ. Neck pain in adolescence. A 4-year follow-up of pain-free preadolescents. Pain. 2004;110(1-2):427-31.

27. NIVEL. Incidentie- prevalentiecijfers in de huisartsenpraktijk: Nivel; 2013. Beschikbaar via www.nivel.nl/incidentie-en-prevalentiecijfers-in-de-huisartsenpraktijk. Geraadpleegd 18 maart 2013.

28. Hollander AEM den, Hoeymans N, Melse JM, Oers JAM van, Polder JJ. Zorg voor gezondheid. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2006.

29. Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Rebbeck T, Lin CW. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2012;184(16):E867-76.

30. Slobbe LCJ, Smit JM, Groen J, Poos MJJC, Kommer GJ. Kosten van ziekten in Nederland 2007. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2011.

31. Silverstein B, Viikari-Juntura E, Kalat J. Use of a prevention index to identify industries at high risk for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, back, and upper extremity in Washington state, 1990-1998. Am J Ind Med. 2002;41(3):149-69.

32. Cote P, Velde G van der, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Holm LW, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S60-74.

33. Cagnie B, Danneels L, Tiggelen D Van, Loose V DE, Cambier D. Individual and work related risk factors for neck pain among office workers: a cross sectional study. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(5):679-86.

34. Minderhoud JM, Keuter EJK, Verhagen AP, Valk M, Rosenbrand CJGM. richtlijn diagnostiek en behandeling van mensen met whiplash associated disorder I/II. Utrecht: NVvN/CBO; 2008.

35. McLean SM, May S, Klaber-Moffett J, Sharp DM, Gardiner E. Risk factors for the onset of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(7):565-72.

36. Zuby DS, Lund AK. Preventing minor neck injuries in rear crashes - forty years of progress. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(4):428-33.

37. Quinlan KP, Annest JL, Myers B, Ryan G, Hill H. Neck strains and sprains among motor vehicle occupants - United States, 2000. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(1):21-7.

38. Vos CJ, Verhagen AP, Passchier J, Koes BW. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute neck pain: an inception cohort study in general practice. Pain Med. 2008;9(5):572-80.

39. Hush JM, Lin CC, Michaleff ZA, Verhagen A, Refshauge KM. Prognosis of acute idiopathic neck pain is poor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(5):824-9.

40. Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Velde G van der, Holm LW, Carragee EJ, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S93-100.

41. Walton DM, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Sterling M, Verhagen AP, Macdermid JC, et al. An Overview of Systematic Reviews on Prognostic Factors in Neck Pain: Results from the International Collaboration on Neck Pain (ICON) Project. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:494-505.

42. Walton D. A review of the definitions of ‘recovery’ used in prognostic studies on whiplash using an ICF framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(12):943-57.

43. Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S83-92.

44. Walton DM, Macdermid JC, Taylor T, Icon. What does ‘recovery’ mean to people with neck pain? Results of a descriptive thematic analysis. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:420-7.

45. Gross AR, Kaplan F, Huang S, Khan M, Santaguida PL, Carlesso LC, et al. Psychological Care, Patient Education, Orthotics, Ergonomics and Prevention Strategies for Neck Pain: An Systematic Overview Update as Part of the ICON Project. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:530-61.

46. Walton DM, Macdermid JC, Santaguida PL, Gross A, Carlesso L, Icon. Results of an International Survey of Practice Patterns for Establishing Prognosis in Neck Pain: The ICON Project. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:387-95.

47. Walton DM, Macdermid JC, Giorgianni AA, Mascarenhas JC, West SC, Zammit CA. Risk factors for persistent problems following acute whiplash injury: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(2):31-43.

48. Schellingerhout JM, Heymans MW, Verhagen AP, Lewis M, Vet HC de, Koes BW. Prognosis of patients with nonspecific neck pain: development and external validation of a prediction rule for persistence of complaints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(17):E827-35.

49. Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J. Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:3.

50. Williams CM, Henschke N, Maher CG, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Macaskill P, et al. Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in patients presenting with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD008643.

51. Stiell IG, Clement CM, O'Connor A, Davies B, Leclair C, Sheehan P, et al. Multicentre prospective validation of use of the Canadian C-Spine Rule by triage nurses in the emergency department. CMAJ. 2010;182(11):1173-9.

52. Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, Brison R, Schull MJ, Rowe BH, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(26):2510-8.

53. Rushton A, Rivett D, Carlesso L, Flynn T, Hing W, Kerry R. international framework for examination of the cervical region for potential of cervical arterial dysfunction prior to orthopaedic manual therapy intervention. IFOMPT; 2012.

54. Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, Teyhen DS, Wainner RS, Whitman JM, et al. neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):A1-A34.

55. Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, Gnann JW, Levin MJ, Backonja M, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 1:S1-26.

56. Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, Clement CM, Lesiuk H, De Maio VJ, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1841-8.

57. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie. KNGF-richtlijn Fysiotherapeutische Dossiervoering. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2016.

58. Andelic N, Johansen JB, Bautz-Holter E, Mengshoel AM, Bakke E, Roe C. Linking self-determined functional problems of patients with neck pain to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:749-55.

59. Lucas N, Macaskill P, Irwig L, Moran R, Bogduk N. Reliability of physical examination for diagnosis of myofascial trigger points: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(1):80-9.

60. Trijffel E van, Anderegg Q, Bossuyt PM, Lucas C. Inter-examiner reliability of passive assessment of intervertebral motion in the cervical and lumbar spine: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2005;10(4):256-69.

61. Cook C, Hegedus E. Diagnostic utility of clinical tests for spinal dysfunction. Man Ther. 2011;16(1):21-5.

62. Shabat S, Leitner Y, David R, Folman Y. The correlation between Spurling test and imaging studies in detecting cervical radiculopathy. J Neuroimaging. 2012;22(4):375-8.

63. Juul T, Langberg H, Enoch F, Sogaard K. The intra- and inter-rater reliability of five clinical muscle performance tests in patients with and without neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:339.

64. Koning CH de, Heuvel SP van den, Staal JB, Smits-Engelsman BC, Hendriks EJ. Clinimetric evaluation of methods to measure muscle functioning in patients with non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:142.

65. Jull GA, O'Leary SP, Falla DL. Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(7):525-33.

66. Swinkels RA, Swinkels-Meewisse IE. Normal values for cervical range of motion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(5):362-7.

67. Koning CH de, Heuvel SP van den, Staal JB, Smits-Engelsman BC, Hendriks EJ. Clinimetric evaluation of active range of motion measures in patients with non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(7):905-21.

68. Strimpakos N. The assessment of the cervical spine. Part 1: Range of motion and proprioception. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15(1):114-24.

69. Williams MA, McCarthy CJ, Chorti A, Cooke MW, Gates S. A systematic review of reliability and validity studies of methods for measuring active and passive cervical range of motion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(2):138-55.

70. Jordan K. Assessment of published reliability studies for cervical spine range-of-motion measurement tools. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(3):180-95.

71. Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Childs JD. Psychometric properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in patients with neck pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(2):109-17.

72. Schmitt MA, Schroder CD, Stenneberg MS, van Meeteren NL, Helders PJ, Pollard B, et al. Content validity of the Dutch version of the Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire. Man Ther. 2013;18(5):386-9.

73. Bolton JE, Humphreys BK. The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. II. Psychometric properties in neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(3):141-8.

74. MacDermid JC, Walton DM, Avery S, Blanchard A, Etruw E, McAlpine C, et al. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(5):400-17.

75. Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1055-68.

76. Domenech MA, Sizer PS, Dedrick GS, McGalliard MK, Brismee JM. The deep neck flexor endurance test: normative data scores in healthy adults. PM R. 2011;3(2):105-10.

77. Edmondston SJ, Wallumrod ME, MacLeid F, Kvamme LS, Joebges S, Brabham GC. Reliability of isometric muscle endurance tests in subjects with postural neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(5):348-54.

78. Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, Eek H van. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62(3):363-72.

79. Ostelo RW, Swinkels-Meewisse IJ, Knol DL, Vlaeyen JW, Vet HC de. Assessing pain and pain-related fear in acute low back pain: what is the smallest detectable change? Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(4):242-8.

80. Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain. 1997;72(1-2):95-7.

81. Parker SL, Godil SS, Shau DN, Mendenhall SK, McGirt MJ. Assessment of the minimum clinically important difference in pain, disability, and quality of life after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(2):154-60.

82. Clark P, Lavielle P, Martinez H. Learning from pain scales: patient perspective. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(7):1584-8.

83. Terluin B, Brouwers EP, Marwijk HW van, Verhaak P, Horst HE van der. Detecting depressive and anxiety disorders in distressed patients in primary care; comparative diagnostic accuracy of the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:58.

84. Terluin B, Marwijk HW van, Ader HJ, Vet HC de, Penninx BW, Hermens ML, et al. The Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ): a validation study of a multidimensional self-report questionnaire to assess distress, depression, anxiety and somatization. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:34.

85. Langerak W, Langeland W, Balkom A van, Draisma S, Terluin B, Draijer N. A validation study of the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) in insurance medicine. Work. 2012;43(3):369-80.

86. Swinkels RAHM, Beurskens AJHM, Meerhoff GA. Raamwerk voor ordening, reductie en selectie van meetinstrumenten. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2013.

87. Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, Dina TS, Mark AS, Wiesel S. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(8):1178-84.

88. Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y, Suzuki N, Nishi Y, Nakamura M, Yabe Y, et al. MRI of cervical intervertebral discs in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):19-24.

89. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie. Overzicht van de formeel door het KNGF ingenomen standpunten ten aanzien van therapieën. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2013.

90. Monticone M, Cedraschi C, Ambrosini E, Rocca B, Fiorentini R, Restelli M, et al. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for subacute and chronic neck pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 May 26;(5):CD010664.

91. Cagnie B, Castelein B, Pollie F, Steelant L, Verhoeyen H, Cools A. Evidence for the use of ischemic compression and dry needling in the management of trigger points of the upper trapezius in patients with neck pain a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2015;94(7):573-83.

92. Ong J, Claydon LS. The effect of dry needling for myofascial trigger points in the neck and shoulders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2014;18(3):390-8.

93. Mejuto-Vazquez MJ, Salom-Moreno J, Ortega-Santiago R, Truyols-Dominguez S, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C. Short-term changes in neck pain, widespread pressure pain sensitivity, and cervical range of motion after the application of trigger point dry needling in patients with acute mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(4):252-60.

94. Graham N, Gross AR, Carlesso LC, Santaguida PL, Macdermid JC, Walton D, et al. An ICON Overview on Physical Modalities for Neck Pain and Associated Disorders. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:440-60.

95. Jeon JH, Jung YJ, Lee JY, Choi JS, Mun JH, Park WY, et al. The effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on myofascial pain syndrome. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(5):665-74.

96. Kroeling P, Gross A, Graham N, Burnie SJ, Szeto G, Goldsmith CH, et al. Electrotherapy for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD004251.

97. Gross A, Miller J, D'Sylva J, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, et al. Manipulation or mobilisation for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(1):CD004249.

98. Gross A, Langevin P, Burnie SJ, Bedard-Brochu MS, Empey B, Dugas E, et al. Manipulation and mobilisation for neck pain contrasted against an inactive control or another active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Sep 23;(9):CD004249.

99. Gross A, Forget M, St George K, Fraser Michelle MH, Graham N, Perry L, et al. Patient education for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;(3):CD005106.

100. Kay TM, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, Rutherford S, Voth S, Hoving JL, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD004250.

101. Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, Klaber Moffett J, Haines T, Burnie SJ, et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(3):CD006408.

102. Taylor RL, O’Brien L, Brown T. A scoping review of the use of elastic therapeutic tape for neck or upper extremity conditions. J Hand Ther. 2014.

103. Vanti C, Bertozzi L, Gardenghi I, Turoni F, Guccione AA, Pillastrini P. Effect of Taping on Spinal Pain and Disability: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Phys Ther. 2015;95(4):493-506.

104. Morris D, Jones D, Ryan H, Ryan CG. The clinical effects of Kinesio(R) Tex taping: A systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29(4):259-70.

105. Mostafavifar M, Wertz J, Borchers J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of kinesio taping for musculoskeletal injury. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(4):33-40.

106. Gross AR, Dziengo S, Boers O, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, Lilge L, et al. Low Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) for Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:396-419.

107. Chow RT, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RA, Bjordal JM. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in the management of neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo or active-treatment controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;374(9705):1897-908.

108. Patel KC, Gross A, Graham N, Goldsmith CH, Ezzo J, Morien A, et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD004871.

109. Gross A, Kay TM, Paquin JP, Blanchette S, Lalonde P, Christie T, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 28;1:CD004250.

110. Graham N, Gross AR, Goldsmith C, Cervical Overview G. Mechanical traction for mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(3):145-52.

111. Griffin XL, Smith N, Parsons N, Costa ML. Ultrasound and shockwave therapy for acute fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008579.

112. Damian M, Zalpour C. Trigger point treatment with radial shock waves in musicians with nonspecific shoulder-neck pain: data from a special physio outpatient clinic for musicians. Med Probl Perform Art. 2011;26(4):211-7.

113. Hoe Victor CW, Urquhart Donna M, Kelsall Helen L, Sim Malcolm R. Ergonomic design and training for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Aug 15;(8):CD008570.

114. Aas R, Tuntland H, Holte K, Røe C, Lund T, Marklund S, et al. Workplace interventions for neck pain in workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Apr 13;(4):CD008160.

115. Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Burdorf A, Stynes SM, de Vet HC, Koes BW. Conservative interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD008742.

116. Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Burdorf A, Stynes Siobhán M, Vet HCW de, Koes Bart W. Conservative interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 12;(12):CD008742.

117. Varatharajan S, Cote P, Shearer HM, Loisel P, Wong JJ, Southerst D, et al. are work disability prevention interventions effective for the management of neck pain or upper extremity disorders? a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):692-708.

118. Coppieters MW, Butler DS. Do ‘sliders’ slide and ‘tensioners’ tension? An analysis of neurodynamic techniques and considerations regarding their application. Man Ther. 2008;13(3):213-21.

119. Boyles R, Toy P, Mellon J, Jr., Hayes M, Hammer B. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(3):135-42.

120. Nee RJ, Vicenzino B, Jull GA, Cleland JA, Coppieters MW. Neural tissue management provides immediate clinically relevant benefits without harmful effects for patients with nerve-related neck and arm pain: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2012;58(1):23-31.

121. Coppieters MW, Stappaerts KH, Wouters LL, Janssens K. The immediate effects of a cervical lateral glide treatment technique in patients with neurogenic cervicobrachial pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(7):369-78.

122. Michaleff ZA, Lin CW, Maher CG, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulation epidemiology: systematic review of cost effectiveness studies. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22(5):655-62.

123. Driessen MT, Lin CW, Tulder MW van. Cost-effectiveness of conservative treatments for neck pain: a systematic review on economic evaluations. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1441-50.

124. Miller J, Gross A, D’Sylva J, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for neck pain: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):334-54.

125. Staal JB, Hendriks EJM, Heijmans M, Kiers H, Lutgers-Boomsma AM, Rutten G, et al. KNGF-richtlijn lage ruglijn. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2013.

126. Balague F. The bone and joint decade (2000-2010) task force on neck pain and its associated disorders: a clinician’s perspective. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S5-6.

127. Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Cheng I, Carroll LJ, Nordin M, Guzman J, et al. Treatment of neck pain: injections and surgical interventions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S153-69.

128. Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Peloso PM, Giles-Smith L, Cheng CS, Greenhalgh SW, et al. Methods for the best evidence synthesis on neck pain and its associated disorders: the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S33-8.

129. Carroll LJ, Hurwitz EL, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Carragee EJ, Nordin M, et al. Research priorities and methodological implications: the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S214-20.

130. Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Peloso P, et al. Clinical practice implications of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders: from concepts and findings to recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S199-213.

131. Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Bone, Joint Decade - Task Force on Neck P, Its Associated D. The empowerment of people with neck pain: introduction: the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S8-S13.

132. Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Nordin M, Guzman J, et al. Treatment of neck pain: noninvasive interventions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S123-52.

133. Reardon R, Haldeman S, Bone, Joint Decade - Task Force on Neck P, Its Associated D. Self-study of values, beliefs, and conflict of interest: the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S24-32.

134. Bryans R, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Duranleau M, Marcoux H, Potter B, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(1):42-63.

135. Verhagen AP, Scholten-Peeters GGGM, Wijngaarden S van, Bie R de, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Conservative treatments for whiplash. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Apr 18;(2):CD003338.

136. Trinh K, Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith Charles H, Wang E, Cameron Ian D, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jul 19;(3):CD004870.

137. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Manuele Therapie. Beroepscompetentieprofiel Manueel Therapeut. Amersfoort: NVMT/KNGF; 2014.

138. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-6.

Algemene informatie

Diagnostisch proces

- Inleiding

- B.1 Anamnese

- B.2 Lichamelijk onderzoek

- B.3 Meetinstrumenten

- B.4 Diagnostische beeldvorming

- B.5 Analyse

- B.6 Premanipulatieve besluitvorming

Therapeutisch proces

- Inleiding

- C.1 Fysiotherapeutische interventies

- C.1.1 Cognitieve gedragstherapie (CBT)/graded activity

- C.1.2 Dry needling

- C.1.3 Elektrotherapie

- C.1.4 Gewrichtsmobilisatie

- C.1.5 Informatie en advies

- C.1.6 (Kinesio)tape

- C.1.7 Lage-intensiteit laser

- C.1.8 Massage

- C.1.9 Medische hulpmiddelen

- C.1.10 Oefentherapie

- C.1.11 Tractie

- C.1.12 Ultrageluid/shockwave

- C.1.13 Warmte- en koudetherapie

- C.1.14 Werkplaatsinterventies

- C.1.15 Zenuwmobilisatietechnieken

- C.2 Manueel-therapeutische interventies

- C.2.1 Manipulatie van de thoracale wervelkolom

- C.2.2 Manipulatie van de cervicale wervelkolom

- C.2.3 Combinatie van manipulatie of mobilisatie en oefentherapie van de cervicale wervelkolom

- C.3 Behandelprofielen

- C.3.1 Behandelprofiel A

- C.3.2 Behandelprofiel B

- C.3.3 Behandelprofiel C

- C.3.4 Behandelprofiel D

- C.4 Afronding van de behandeling